The Guardian Trees of Ireland

Irish and Celtic myths and legends, Irish folklore and Irish fairy tales from the Historical Cycle

Ancient and mysterious trees of Ireland

Ancient are the hills and mountains of Ireland, and ancient are her trees, something that the old people who lived here knew well. To them a tree was a mystical thing with its roots reaching down into the underworld of the sidhe mounds, and its branches lifting up high into the heavens towards the sun, moon and stars. Well over ten thousand places in Ireland today have a tree in their names, such as Moycullen, the plain of the holly, and Newry, the yew at the hard of the strand.

Ancient are the hills and mountains of Ireland, and ancient are her trees, something that the old people who lived here knew well. To them a tree was a mystical thing with its roots reaching down into the underworld of the sidhe mounds, and its branches lifting up high into the heavens towards the sun, moon and stars. Well over ten thousand places in Ireland today have a tree in their names, such as Moycullen, the plain of the holly, and Newry, the yew at the hard of the strand.

Trees were seen as crossroads and doorways to the spirit world, and not a king was crowned nor a chieftain granted authority unless it was beneath the leaves of their clan tree, from whose branches was cut a rod, the slat na righe, to show their authority. As the tree or bile flourished, so did the people of the land, and so a clan tree was said to shelter thousands of men.

Fionn MacCumhaill's name means “son of the hazel”, for hazel nuts were believed to represent knowledge, and you could count the number of them a salmon had eaten by counting the spots on his back.

But the kings of all of the trees of Ireland were the five guardian trees, protectors of the five provinces. As it was told, a mighty giant came to the court of High King Conan Bececlach, known for his wisdom and even-handed justice, bearing with him a strange staff of many fruits, including the apple, the acorn and the hazelnut.

As tall as a tree himself he was, with golden locks flowing to his knees, clad in a shimmering white robe, and the sun and sky could be seen between his legs, so mighty was he.

Well his name was Trefuilngid Treochair, and it was plain to see he was not of this world!

He called together all the people of Ireland, and chose the seven wisest from each quarter, and seven more from Tara, the King's province. Many strange sciences and arts he taught them, and secrets from times long past, forgotten by even the oldest and wisest of owls, whose mysteries slumber now beneath the ocean waves, or in the chambers of the deepest caves.

After that, he gave the fruits from his staff to Fintan, the white haired eldest, who put his druidic craft to good use, taking the seeds from the fruit and planting one in each corner of Ireland, and one more in Tara, that was called Temair, at Uisneach.

These trees became the five guardians of Ireland, and long and long they stood.

Eó Mugna was one of the sons of the tree of knowledge, which stood in the garden of Eden. His name meant yew but in fact he was an oak of immense size and girth. This tree sprang from the staff itself, and bore apples, acorns and hazelnuts. The tree stood at Bealach Mughna, on the plain of Magh Ailbhe, which today we call Ballaghmoon, Co Kildare.

Bile Tortan was a tall and straight ash, and it grew at Ard Breccan in Navan, while Eó Ruis stood at Leighlin, County Carlow, and Craeb Daithí, another ash, spread its many branches at Farbill, County Westmeath.

The central tree at Tara was Craeb Uisnig or Uisneach, and it grew on a hill at the heart of Mide, the King's country. This place was thought to be the very centre of Ireland, where all five provinces touched, and it cast its shadow over Ail na Mirean, the Stone of Divisions.

How these trees fell is not known, but it is said to have happened during the joint reign of the brothers Diarmait and Blathmac, sons of Áed Sláine, who both died in in the middle of the seventh century.

Of course Ireland in those times was far from a peaceful place, it is sorry to say, and since the power and wellbeing of a king and his people was connected to their sacred tree, other tribes and clans would sometimes attack and uproot the trees! And by this they demonstrated their power and mastery over their enemies.

In the twelfth century, the cherished red birch of the Ui Fiachra Aidhne of Galway was destroyed, while in the eleventh century the ancient annals tell us that the O'Loughlins, who had sworn fealty to the infamous O'Neills, invaded Ulster and hewed their tree, Craebh-Tulcha, from its roots.

Twelve years later the Ulidian Ulstermen had their vengeance, raiding O'Neill lands and cutting down the entire sacred grove of Tulach Óc, where the O'Neill kings were crowned. Not that the O'Neills took that sitting down, for they reaped a harvest of three thousand cattle from the raiders not long after, a steep prince to pay indeed back in those days. In the tenth century, the tree of Magh Adhair in Clare, where the O'Briens held sway, was destroyed by the High King himself!

Not alone in their veneration of trees were the Gaels, for the Norse reavers who troubled this green land also held their dark ceremonies under the boughs of consecrated groves. These were the dreaded blóts, where human and animal sacrifices were hung in worship of their heathen gods.

It was for this reason that the High King of Ireland, Brian Bóruma, who drove the Vikings out once and for all, sent a group of his men to Caill Tomair after he had defeated Sitric Silkbeard the Viking slaver lord. Caill Tomair, meaning “Thor's wood”, was a sacred place to the Vikings, and it was there they had worked the blóts.

Needless to say, there wasn't much of it left standing after Brian Ború's men were through with it!

So important were trees to the people of Ireland that the Brehon laws, some of the earliest and most sophisticated laws in Europe, had many rules devoted to them. Even the felling of a chieftain tree was considered the same as killing a chieftain!

The laws of the poets divided trees into four kinds, the airig fedo, nobles of the wood, the aithig fedo or commoners, the fodla fedo, the lower divisions and the losa fedo, or bushes.

The book Bretha Comaithchesa, which means “neighbourhood judgements” from the eighth century or thereabouts, tells us of the different penalties applied for damaging the branches or bark of tree from each rank, and for cutting one down. It was usually the case that dire or punishments were levied as livestock, so if you cut down a noble tree, that would cost you two and half good cows, while for a commoner, it was one cow, and so it went.

Even the alphabet, when the people of Ireland began writing, was deeply connected to their reverence for trees. This was the Ogham, where each letter had a name and a riddle which led back to the meaning of the letter, and many of these letters meant different kinds of trees. Very fond of riddles they were, perhaps considering them the best way to keep knowledge from unprepared minds.

It was said that the ancient Sidhe Ogma sun-face, or the Ogham lord, raised four pillars of equal length, and upon them he wrote the signs of the Ogham. His followers or those who sought his favour would have a slender golden chain attached from the tip of their tongue to their ears, to symbolise his eloquence and honeyed mastery of language.

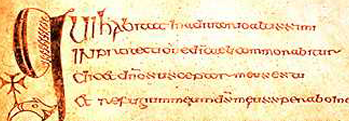

As is recorded in Auraicept na n-Éces, a 7th-century work of Irish grammar, written by a scholar named Longarad, words in Ogham are to be read from right to left and from the bottom to the top.

“This is their number: there are five groups of Ogham and each group has five letters, and each of them has from one to five scores, and their orientations distinguish them. Their orientations are: right of the stemline, left of the stemline, around the stemline, through the stemline, across the stemline. Ogham is climbed as a tree is climbed, i.e. treading on the root of the tree first with one’s right hand before and one’s left hand last. After that it is across it and against it and through it and around it.”

Ogham itself is a mysterious and complex script, and it would take a poet of old three years to learn each variety, fifty each year. By this means were secrets passed around and hidden lore kept hidden. Some were written in circles, others in rectangles, some on crosses or wavy lines, and warriors would have their own Ogham.

These are the twenty eight trees and bushes mentioned in Brehon law:

The Airig Fedo, or Lords of the Wood

- Dair, oak

- Coll, hazel

- Cuilenn, holly

- Ibar, yew

- Uinnius, ash

- Ochtach, Scots pine

- Aball, wild apple-tree

The Aithig Fhedo, Commoners of the Wood

- Fern, alder

- Sail, willow, sally

- Scé, whitethorn, hawthorn

- Cáerthann, rowan

- Beithe, birch

- Lem, elm

- Idath, wild cherry

The Fodla Fedo or the Lower Inhabitants of the Wood

- Draigen, blackthorn

- Trom, elder

- Féorus, spindle-tree

- Findcholl, whitebeam

- Caithne, arbutus, strawberry tree

- Crithach, aspen

- Crann fir, juniper

And lastly, the Losa Fedo, the Bushes of the Wood.

- Raith, bracken

- Rait, bog-myrtle

- Aitenn, furze, gorse, whin

- Dris, bramble

- Fróech, heather

- Gilcach, broom

- Spín, wild rose

In one of the earliest tongues of Ireland, the oak was known as daru or derwa, and it has been used to build the foundations of crannógs, the lake dwelling places of the ancient Irish, as well as their toghers, trackways and paths across bogs and uncertain ground. Oak gall was used for the making of black dye.

Hazel nuts and hazel wood were both of great importance to the old people. The name-story for Tara tells that it was a hazel wood known as Fordruim. If you wanted to join the Fianna warrior bands, you had to protect yourself against many attacks using only a hazel rod and shield. It was forbidden to burn hazel, since it was the poet's wood, and some said it was a fairy tree.

Hazel nuts were called the nuts of wisdom, and seven hazel trees grew at the wellspring of the seven chief rivers of Ireland. Nine more grew over Connla's well and the well of Segais, and it was by eating a salmon who had partaken of their nuts that Fionn gained his legendary knowledge.

From yew or apple was the wand of the druid made, and nine of the rooms in the place of Cráebruad had nine rooms lined with red yew for the pleasure of Conchobar Mac Neasa.

The ash was greatly respected, as it made long, straight, unbreaking shafts for spears and staves, and people would often refuse to cut down an ash tree in case their own homes might be burned by the sidhe! More than half of the sacred guardian trees of Ireland were ash, and they are sometimes planting in places of particular importance.

The apple tree was meant to hold the keys to immortality, and the fairy island of Emain Ablach was known as the land of the apples, and it was meant to be a favoured food of the fairies. Cúchulainn once followed a rolling apple to freedom.

The rowan stopped the dead from rising, puts wings under a dog, and stopped fire from taking hold of a home. Its protective qualities meant ti was planted next to churches and homes throughout the country.

The alder was credited with many healing powers since its white wood turns red when cut.

The hawthorn, the May bush or white thorn bus, the sacred scéach, was known to be a fairy meeting tree, and should you find one standing alone, it would not be a good idea to cut it down! You can sometimes tell when you're looking at a fairy tree rather than a normal tree because it is narrow and divides into three bushes from the one trunk, and the branches might look like human limbs. Often as well you may spot a fairy path because it will go from one hawthorn to the next!

On the map below can be found the place where Craeb Uisnig, the central guardian tree of Ireland, once grew.

More Tales from the Historical Cycle

The gift of the gab, as it’s known, is a common thing among the Irish – being able to talk all day about anything and everything, and do it in a way that would have you listen as well. It’s as Irish as red hair and freckles. But what if you didn’t have the gift of the gab, or felt a deficiency of gabbiness? Never fear, al ... [more]

Ireland is full of strange little corners and odd byways that only a few know about, and one such is a mysterious place called the Gearagh, or An Gaorthadh, meaning the wooded river bed, in County Cork. Once it was part of the first forests in Ireland, home to verdant giants that grew after the great ice melted away, but now all that remains is a s ... [more]

Ireland at the beginning of the first millenium was a turbulent place, with many clans and kingdoms fighting among themselves, so that a Lord might be sitting comfortably one day but find himself fleeing for his life the next! And so it was with one of the greatest of Ireland's kings, Cormac Mac Art. Although he was by blood, law and custom ... [more]

On Martinmas eve, that is to say the 10th of November, it used to be the custom in many parts of Ireland to sacrifice an animal to Saint Martin of Tours! This tradition has only recently ceased, having been carried on well into living memory, as lately as the 1940s in some places. In poorer homes a goose, gander, duck or chicken was killed, whil ... [more]

It's true to say that music has a magic all to itself, for it can transport us to different places and times with the strumming of a few notes. It can make us feel angry, or sad, or happy, or any one of a myriad of other emotions. But if you were to hear the music of an occult Sidhe instrument played by one of the fairy folk under a loon's ... [more]

King Cormac Mac Airt was one of the mightiest kings of Ireland, known and well known for his wisdom, but after he lost an eye in a battle with the Déisi, he had to step down, for the solemn law was that a king must be without blemish. His son Cairbre came to him to ask his advice before in turn being crowned king. “O Cormac, grandso ... [more]

"Crom Cruach and his sub-gods twelve," Said Cormac "are but carven treene; The axe that made them, haft or helve, Had worthier of our worship been. "But He who made the tree to grow, And hid in earth the iron-stone, And made the man with mind to know The axe's use, is God alone." Anon to priests of Crom was ... [more]

Most people with an interest in Irish mythology and legends will have heard of the great tale of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, which tells of the heroic deeds of Cú Chulainn as he resisted and gave battle single handed to the armies of Queen Medb. What most don't know is that the ancient tale was once all but lost, for th ... [more]

One of the most legended and powerful relics of ancient Ireland was the Cathach, or battle-book of St Colmcille, who was also known as St Columba. A Cathach was really any sort of sacred or magical artifact, and great was the strife between the tribes and clans of Ireland to gain ownership of them! The psalter or prayer book of Saint Colmcille w ... [more]

Three was a sacred number to the people of ancient Ireland, bearing with it a hint of magic and the sacred, and this belief carried through to their spiritual practices, which occasionally included human sacrifice! Most cultures throughout history have at one point or another practised some form of human sacrifice, and lurid tales passed down fr ... [more]

Saint Colman was a famous Saint in early Irish Christianity, being born a prince not long after Saint Patrick brought the faith to Ireland in the first place. Despite his royal lineage however, his birth was no easy matter, for the druids had prophecised darkly that he would be a great man and surpass all others of his clan! His pregnant mother ... [more]

The old pagan times in Ireland were fraught with peril for even the mightiest warriors, with chieftains and tribes going to war often and for many reasons – pride, hatred, love and greed! And so it was with the fierce King Conall Collomrach. Little is known of his exploits, but his reign was brief and his end was violent, leaving behind only ... [more]

This now is the true tale of mighty King Cathal Mac Finguine of Munster, lord of Cork and warrior without peer. In ancient Ireland this story was told when mead was first brought out, or a prince sat to his feast, or when an inheritance was taken, and the reward for reciting this story was a white-spotted, red-eared cow, a shirt of new linen, or a ... [more]

The river in Meath which we today know as the Delvin, that very same river which flows into the Irish sea in Gormanstown, was not always called so. In the time of Kings it was called Inbher Oillbine, and this is the grim story of how it got that name. There was a prince who lived near to the mouth of the river, and his name was Ruadh Mac Righdui ... [more]

The boy who was to be Saint Colman was born in the northern kingdom of Dalriada, which held both Northern Ireland and Scotland in its power at the start of the sixth century. This was the time of the dawn of Christianity in Ireland, and it was a time when great terrors and monsters from primordial epochs still swam in the deep lakes and lazy rivers ... [more]

Most people have heard of Ireland's famous title, “The Island of Saints and Scholars”, and the reason it was so well known was because of the many fine Irish Catholic universities and colleges that preserved and spread learning throughout Europe. Of them all, there were few finer than the one in Howth, and so wonderful was its reput ... [more]

Very often here in Ireland we walk past the most astonishing buildings, carven stone high crosses, ancient temples and many similar things, but rarely do we wonder who built them. Well as it turns out, legend has it that a surprising number of them were built by a man called Gobán Saor, whose name means “Gobán the Builder,&rdquo ... [more]

I. Once upon a time there was a High King in Ireland by the name of Conn the hundred-fighter, for so many battles had he fought and won to gain his kingship. At the end of his reign was Fionn Mac Cumhaill born. Long was Conn's lineage, although I won't trouble you with the details, but he reigned at Tara of the Kings as Lord of all Irela ... [more]

In the time of High King Lugaid Luaigne, that is around the age when Fionn Mac Cumhaill and his Fianna fought in defence of the great land of Ireland, a dispute arose in the northern Kingdom among the men of the Ulaid, for instead of there being only one king of Ulster, there were two! Well, as anyone who knows anything about kings will tell you ... [more]

St Colmcille is one of the three patron saints of Ireland, and his life is the subject of story and legend. It was by his efforts that Christianity spread not only through Ireland but also Scotland, England and parts of Europe too! He was a tall and powerfully built man with a rich and melodious voice which, it was said, could be heard from one hil ... [more]

From the earliest times and in every corner of the world, mead was held in reverence. This sweet tasting fermented honey drink was especially loved by the ancient Irish, who shared fireside stories about rivers of mead in mystical lands over the edge of the ocean's horizon, ruled by Mannanan Mac Lír, and even in the place where the dead ... [more]

Ancient are the hills and mountains of Ireland, and ancient are her trees, something that the old people who lived here knew well. To them a tree was a mystical thing with its roots reaching down into the underworld of the sidhe mounds, and its branches lifting up high into the heavens towards the sun, moon and stars. Well over ten thousand places ... [more]

The Irish bee has been a beloved part of the culture and folklore as long as there have been people in Ireland, producing honey for cakes and mead as well as beeswax which has no end of uses. Many's the warm summer evening has been filled with their gentle humming above the beautiful flowers they help to pollinate. And yet for all that, old ... [more]

As Saint Patrick travelled across Ireland, spreading Christianity and the light among the pagan tribes, he saw many wonders and defeated many evils, but always more rose up to challenge him. So he took himself to prayer and saw a vision that he should travel to Croagh Patrick – although it was not so known at that time – and spend the L ... [more]

The shifting shadows of pagan times held sway over Ireland when the High King was a man known as Laoghaire, famed for his merciless fury and great strength, and he sat upon the seat of the High Kings in Tara. But unknown to him, Saint Patrick had landed in a little boat at Colpe in the Boyne estuary, travelling to a place called Ferta fer Feic, or ... [more]

One of the three patron Saints of Ireland, along with Patrick and Colmcille, St Brigid of Kildare was a devout Catholic in the very first days of the faith in Ireland. Her feast day is the first of February, which previously had been the pagan festival of Imbolc, halfway between winter and spring. Brigid herself was the daughter of a baptised Ch ... [more]

Through many an ancient legend and tale rings the name of the fierce and powerful druid called Mogh Ruith, meaning “slave of the wheel”. Older legends make him out to be the king of the Fir Bolg, or a druid gifted with many lives by the fairies, or that the name was but a title passed down through generations. Some say he had one eye ... [more]

Ireland has had many high kings, some were wise and kind and others cruel and the holders of grudges, but there were few as great as High King Cormac Mac Art, grandson of Conn of the Hundred Battles and son of Art and Ectach, the daughter of a mighty blacksmith. In his youth he stayed at the hall of the king of the north, Fergus Dubhdedach, but ... [more]

Back in the days of old Ireland when legends walked the earth, before the light drove back the shadows of ancient aeons, the word of a bard was much feared, for the people had no writing, so all of their culture and histories were held in songs and poems by bardic masters. As you can imagine even the mightiest were wary of getting on the wrong s ... [more]

In ancient days there was an Irish King whose name was Labraid Lioseach, known also as Labraid the Sailor for a long voyage he took into fairy seas, and when he came back from that voyage he was never seen without a deep hood over his head, except by one man. That man saw him once a year to trim his hair, and after the King's hair was cut, t ... [more]

It was the custom in Ireland of old to lay geases upon champions, heroes and warriors. These were magical forbiddings, deeds they must not do or disaster would follow, and no disaster fell so hard upon a man who broke his geases as upon Conaire Mor! His mother was a woman of the Sidhe called Etain, who had been married to King Eochaid, but disco ... [more]

Tierna the Historian was one of the many chroniclers and monks who wrote the tales of ancient Irish legends, telling us of strange and notable events in the almost forgotten past, the deeds of heroes and kings, and in one case, the disappearance of the High king himself! For it was by Tierna's hand we know that High King Cormac went missing for ... [more]

In the time between the Tuatha Princes and St Patrick, there rose over the people of Ireland mighty High Kings, who held power by force of arms, wit and wisdom. One of the greatest among them was Cormac of the wide purple cloak, whose hair was as golden as the heavy torc around his neck, with teeth like a shower of pearls and skin as fair as snow. ... [more]

Long ago when the fierce Milesians invaded Ireland and defeated the De Danann after many wars and battles, despite their sorceries and all their courage, skill and sciences, the folk of Danann made for themselves eldritch amulets and charms by which they and all their possessions became invisible to mortals, and so they continued to lead their old ... [more]

The Tailteann games were a grand affair in Ireland once upon a time, every bit as celebrated and renowned as the Olympics are today. Having their roots thousands of years earlier, in the time of the Tuatha Dé Danann, lakes were made and gigantic fires were lit during Lughnasadh, the summer feast in July. Druids and poets would compose cea ... [more]

The Claddagh Ring is one of those well known emblems of Ireland that most people recognise, but how many know the stories behind it? Many's the young man has gifted one to his lady, giving his heart along with it, as did the ring's original maker. Back in the seventeenth century there was a young Irish lad by the name of Richard Joyce, w ... [more]

Ah Tara, Temair of old, seat of more than a hundred High Kings of Ireland for better than a thousand years, home to the royal lines of Cormac and Tuathal, where is your wisdom and beauty? Where are the mighty warriors and poets who once danced in your halls? Why now do cattle and livestock graze where the mighty Fionn faced the Tuatha sidhe with a ... [more]

On Easter Sunday morning, in anno domine 433 it was that Patrick came face to face with the beating heart of the old religion at Tara, and did battle with the Druids. Although some might dispute the miraculous nature of the events that took place on that day, few argue they didn't happen, so take from that what you will! Laeghaire the king a ... [more]

Brian Boru was one of the greatest High Kings of all Ireland, a Christian king whose small dynasty challenged and broke even the power of the O'Neills, who had ruled Ireland from time immemorial. He rose to prominence at a time when the cruel Norseman was pillaging the lands of both Ireland and England, slaughtering and slave-taking, barbarians ... [more]

King Suibhne was master of the northern land of Dalriada in Ulster, and a grim and fierce king he was too, yet fair to behold like palest snow, with deep blue eyes. A mighty master at arms, he was called to war often, but latterly to the bloody battle of Moy Rath. As he readied himself he heard in the distance a church bell ringing, and no man of G ... [more]